Saturday, 24 May 2025

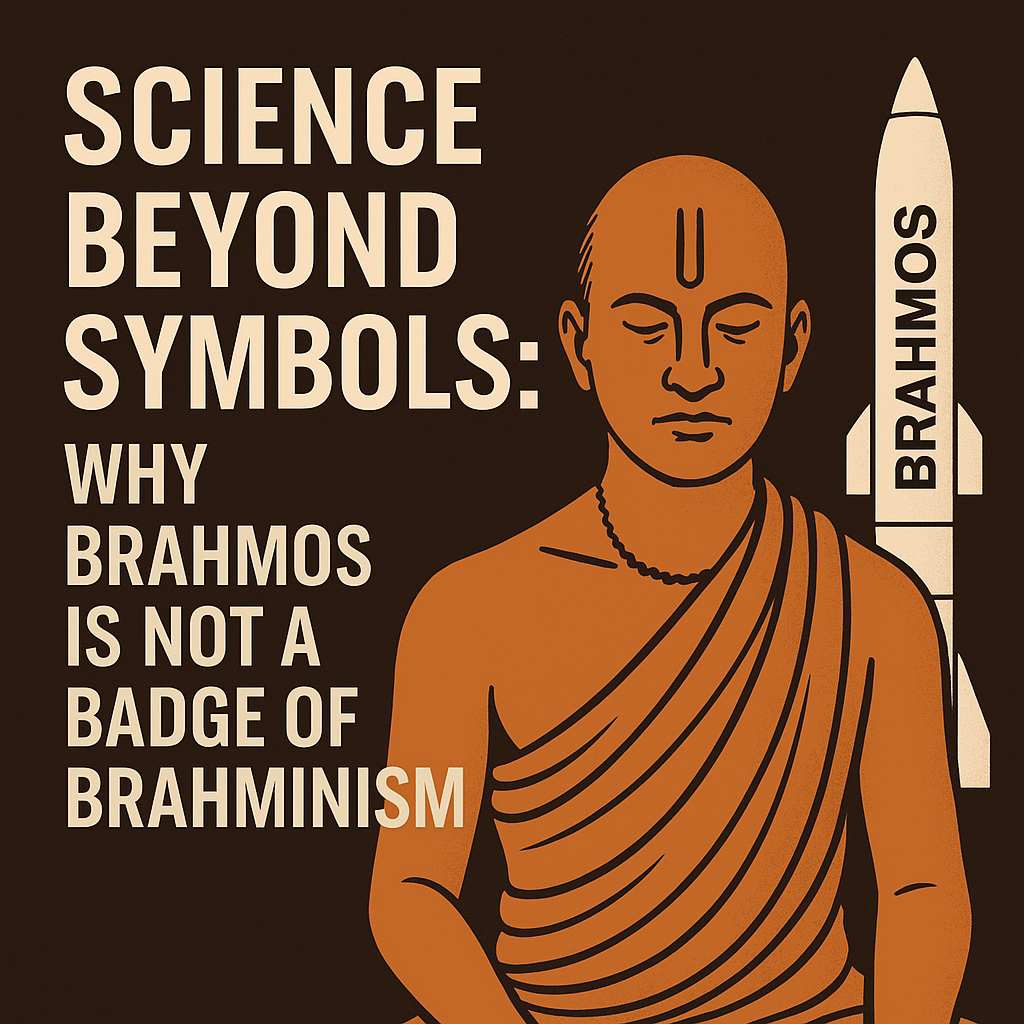

Science Beyond Symbols

Thursday, 22 May 2025

Economic Darwinism

Economic Darwinism: Why Human Progress Still Runs on Primal Instincts

1. मानव व्यवहार में असमानता: प्राकृतिक प्रवृत्ति या पशुवृत्ति?

वैश्विक व्यवस्था

में मानव

व्यवहार की

मूलभूत विषमता

स्पष्ट रूप

से देखी

जा सकती

है। यह

एक ऐसा

"प्राकृतिक चयन"

या "आर्थिक

डार्विनवाद" है

जहाँ बड़े

राष्ट्रों और

प्रभुत्वशाली अर्थव्यवस्थाओं

के लिए

अंतर्राष्ट्रीय नियम

और आर्थिक

नीतियाँ अलग

ढंग से

कार्य करती

हैं, जबकि

छोटे देश

या विकासशील

अर्थव्यवस्थाएँ असमान

व्यापार समझौतों,

सत्ता की

गतिशीलता और

शोषण का

शिकार होती

हैं। यह

व्यवहार "बाज़ार

की अदृश्य

शक्ति" के

सिद्धांत से

मिलता-जुलता

है—जैसे

यह छोटे

खिलाड़ियों को

बड़े पूँजीवादी

संस्थानों के

समक्ष असहाय

बना देती

है। यह

स्थिति एक

प्रकार के

"जंगल-राज"

की तरह

है, जहाँ

मजबूत अर्थव्यवस्थाएँ

कमज़ोर अर्थव्यवस्थाओं

का शोषण

करती हैं

और उन्हें

निगल जाती

हैं—ठीक

वैसे ही

जैसे बड़ी

मछलियाँ छोटी

मछलियों को

निगल जाती

हैं। यह

व्यवहार कदाचित्

पशुवृत्ति से

उपजा है

और अब

केवल प्राकृतिक

ही नहीं,

बल्कि वैश्विक

अर्थनीति का

भी अभिन्न

हिस्सा बन

चुका है।

2. फ्रायड का सिद्धांत: क्या सभ्यता ने हमें बदला?

सिग्मंड फ्रायड

ने माना

था कि

सभ्यता मनुष्य

को उसकी

क्रूर प्रवृत्तियों

और मूल

instincts

से दूर

ले जाएगी,

उसे अधिक

संयमशील बनाएगी।

उन्होंने सोचा

था कि

जैसे-जैसे

मानव सुसंकृत

(civilized)

होता जाएगा,

वह इस

"जंगलिपन"

या "प्राकृतिक

व्यवहार" पर

काबू पाता

जाएगा। परन्तु,

आधुनिक इतिहास

इसके विपरीत

चित्र प्रस्तुत

करता है

और फ्रायड

की यह

बात अभी

तो साची

पडती हुई

नहीं लगती।

द्वितीय विश्वयुद्ध

में हुई

रणनीतिक तबाही

और आज

के आर्थिक

युद्ध (Economic

Warfare) जैसे आर्थिक

नाकाबंदी/प्रतिबंधों

(sanctions),

व्यापारिक शुल्क

नीतियों (tariffs),

मुद्रा हेरफेर

(currency

manipulation) और उपभोक्ता

बहिष्कार (boycott)

की प्रवृत्तियाँ

दर्शाती हैं

कि सभ्यता

के आवरण

के नीचे

भी आक्रामकता

और वर्चस्व

की भूख

यथावत है।

यह व्यवहार

"नव-उपनिवेशवाद"

का रूपांतरण

है और

द्वितीय विश्वयुद्ध

के यथार्थवादी

राजनीति (Realpolitik)

और आज

के भू-आर्थिक

संघर्ष (Geoeconomic

Rivalries) में केवल

हथियारों का

स्वरूप बदला

है।

3. क्या आर्थिक युद्ध सभ्यता की प्रगति है?

युद्ध की

प्रवृत्ति अब

सीधे हथियारों

से नहीं,

बल्कि आर्थिक

उपायों से

प्रकट होती

है। टैरिफ

युद्ध, निर्यात-आधारित

नियंत्रण, उपभोक्ता

बहिष्कार—ये

उपाय बेशक,

नरसंहार से

मुक्त हैं।

और इस

अर्थ में,

यह पुराने

युद्धों की

तुलना में

"काफी

बेहतर" कहे

जा सकते

हैं तथा

मानव की

"सभ्यता

की ओर

गति" माने

जा सकते

हैं। अमेरिका

द्वारा छेड़ा

गया टैरिफ

युद्ध यदि

आर्थिक गुफामानवता

का उदाहरण

है, तो

भारत जैसे

देशों द्वारा

अपनाई गई

रणनीतिक बहिष्कार

नीति एक

आत्मरक्षात्मक "नव-आर्थिक

युद्ध" की

ओर संकेत

करती है।

यहाँ तक

कि बहुसंख्यकवादी

नीतियाँ (Majoritarian

Policies) का उपयोग

आर्थिक प्रभुत्व

स्थापित करने

के लिए

या बचाव

के लिए

एक हथियार

के रूप

में हो

रहा है।

यह सही

है कि

इनके विनाशकारी

प्रभाव कम

नहीं हैं।

हालाँकि, यह

पूरी तरह

"शून्य-योग

खेल" (Zero-Sum

Game) नहीं है,

क्योंकि वैश्विक

आपूर्ति श्रृंखलाएँ

(Global

Supply Chains) और अंतर्निर्भरता

(Interdependence)

इस युग

की वास्तविकताएँ

हैं।

4. क्या हम इससे आगे निकल पाएँगे?

मानवता क्या

इससे आगे

निकल सकती

है? बिलकुल

निकल सकती

है, परन्तु

यथास्थिति में

बदलाव की

कीमत चुकानी

पड़ती है।

इतिहास गवाह

है कि

बड़े बदलाव

बड़े बलिदान

मांगते हैं।

जिस प्रकार

20वीं

सदी की

महामंदी और

विश्वयुद्धों तथा

असंख्य छोटे

युद्धों में

बलिदान देने

के पश्चात

ब्रैटन वुड्स

संस्थानों, संयुक्त

राष्ट्र, और

टिकाऊ विकास

लक्ष्यों (SDGs)

की अवधारणाएँ

उभरीं, जिन्होंने

वैश्विक शांति

और विकास

को बढ़ावा

दिया और

हमने इनमें

अच्छी सफलता

भी पाई।

उसी तरह,

आज, COVID-19 के

बाद के

आर्थिक झटके,

यूक्रेन संकट,

और वर्तमान

आर्थिक उथल-पुथल

एक नई

वैश्विक वित्तीय

वास्तुकला और

संतुलित वैश्विक

आर्थिक व्यवस्था

की माँग

कर रहे

हैं। ऐसा

लग रहा

है कि

21वीं

सदी में

भी एक

भीषण आर्थिक

उथल-पुथल

या "बड़ी

आर्थिक खूनामर्की"

के बाद

ही नये

युग का

निर्माण संभव

होगा।

5. निष्कर्ष: मानवता की यात्रा अधूरी है

21वीं सदी

की चुनौती

"डिजिटल

उपनिवेशवाद" और

"डेटा साम्राज्यवाद"

से लड़ना

है। क्रिप्टोकरेंसी

(Crypto

Currencies), कृत्रिम बुद्धिमत्ता

(AI),

और ब्लॉकचेन

प्रौद्योगिकी (Blockchain)

जैसे साधन

नए हथियार

हैं। आज

की दुनिया

मूल प्रवृत्तियों

और वैश्विक

नैतिकता के

दो छोरों

पर झूल

रही है।

परन्तु, इतिहास

यह दर्शाता

है कि

हर आर्थिक

मंदी, हर

वित्तीय संकट,

और हर

नीतिगत टकराव

ने मानवता

को एक

नये सोच,

नये ढांचे

और साझा

समृद्धि के

सिद्धांत की

ओर अग्रसर

किया है।

न्यायसंगत वैश्वीकरण

(Equitable

Globalization) और बहुपक्षवाद

(Multilateralism)

ही टिकाऊ

समाधान हैं।

मानवता आर्थिक

नैतिकता की

ओर बढ़

रही है।

हम इन

वर्तमान आर्थिक

संघर्षों से

भी बाहर

निकलेंगे। हो

सकता है,

आने वाला

युग भूख

और युद्ध

के हथियारों

की जगह

नीतिगत सहयोग,

वित्तीय न्याय

और समावेशी

विकास को

हथियार बनाए।

Wednesday, 21 May 2025

Nolan Oppenheimer

Christopher Nolan's ‘Oppenheimer’: A Cinematic Synthesis of Narrative Innovation, Political Intrigue, and Myth-philosophical Resonance

Christopher Nolan’s Oppenheimer (2023)

redefines the biopic genre by merging nonlinear storytelling, political

critique, and mythological allegory to interrogate the ethical dilemmas of

scientific progress. This article examines how Nolan’s narrative

techniques—fragmented chronology, subjective perspective, and auditory-visual

symbolism—construct a dialectic between intellect and wisdom, embodied in the

cinematic portrayals of J. Robert Oppenheimer and Albert Einstein. By situating

the film within its historical-political context (the Manhattan Project, Cold

War paranoia, and McCarthyism), the analysis reveals how Nolan critiques the

weaponization of science by ideological forces. Furthermore, the study explores

the film’s invocation of the Promethean myth, framing Oppenheimer as a tragic

figure whose genius becomes both a transformative and destructive force.

Ultimately, Oppenheimer emerges as a philosophical inquiry

into the moral limits of human innovation, using cinema not just to depict

history but to question its recurring ethical crises.

Keywords: Christopher Nolan, Oppenheimer,

narrative structure, political ideology, Promethean myth, scientific ethics,

Albert Einstein, atomic age, nonlinear storytelling, cinematic allegory

Monday, 19 May 2025

AI Generated Podcast on NAAC

Experimenting with AI Tools for Academic Communication:

Podcast on NAAC’s New Accreditation System

As part of my ongoing engagement with AI tools for educational innovation, I recently explored a new workflow to create and publish a podcast-based explainer on the National Assessment and Accreditation Council (NAAC)’s proposed new accreditation system. This initiative aligns with the growing need to simplify complex policy documents and reforms for a wider academic audience.

To create the content, I used Google NotebookLM — a powerful AI-powered note-taking and summarization tool. By uploading relevant documents and reports about the proposed changes in NAAC's accreditation framework, I was able to prompt NotebookLM to generate a clear, structured podcast script. The tool’s capacity to synthesize technical information into coherent narrative form made it especially effective for this task.

Once the podcast script was finalized and recorded, I turned to Audiogram — an AI platform that converts audio content into engaging, captioned videos optimized for social media and video-sharing platforms. This step allowed me to create a visually enriched, accessible version of the podcast suitable for YouTube publication, complete with on-screen captions for better comprehension and outreach.

In this blog post, I am pleased to share the captioned video podcast, which provides an overview of NAAC’s proposed changes, potential implications for higher education institutions, and the broader context of accreditation reform in India.

🎥 Watch the Video Podcast Here:

This experiment highlights how AI tools can significantly streamline the process of content creation, curation, and dissemination — especially for educators and administrators navigating evolving academic landscapes.

I invite you to watch the video, share your feedback, and reflect on how such tools might be integrated into your own teaching, training, or institutional development efforts.