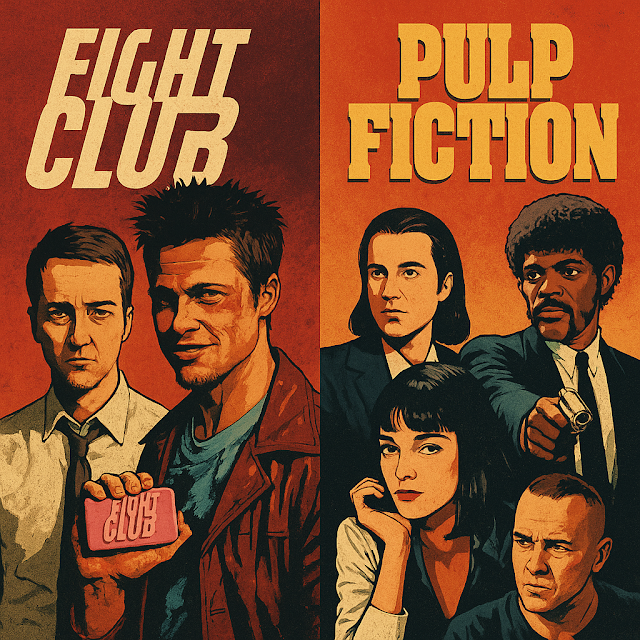

Revisiting Cult Classics: The Enduring Relevance of Fight Club and Pulp Fiction

Rewatching David Fincher’s Fight Club (1999) and Quentin Tarantino’s Pulp Fiction (1994) after two decades is like peeling away the layers of cinematic history to reveal how deeply these films have etched themselves into the cultural psyche. Despite the time gap, both these seminal works remain startlingly fresh, subversively relevant, and cinematically compelling. Their influence on global and Indian filmmaking is not only visible in stylistic mimicry but in the very grammar of postmodern cinema that these films helped to define.

At the heart of their cult status lies their trenchant critique of late capitalism, consumer culture, and modern identity. In Fight Club, Edward Norton’s unnamed narrator—fractured, alienated, and numbed by the vacuity of corporate life—embodies the postmodern subject lost in the simulacrum of advertising and brand fetishism. The film’s anarchist alter ego, Tyler Durden, functions not merely as a character but as an ideological specter—part Nietzschean Übermensch, part Situationist rebel—who exposes the hollow promise of individualism under neoliberalism. His iconic lines like “The things you own end up owning you” continue to resonate in a world even more commodified than the one Fincher depicted.

Tarantino’s Pulp Fiction, on the other hand, revolutionized narrative form itself. The film deconstructs linear storytelling, embracing the in medias res structure, temporal disjunction, and multiple character arcs that challenge traditional narrative coherence. This kind of narrative fragmentation—akin to Bakhtin’s concept of heteroglossia and Barthes' idea of the writerly text—demands active spectatorship and reflects the fragmented reality of postmodern life. Characters like Jules Winnfield, Vincent Vega, Mia Wallace, and Butch Coolidge are not merely characters but stylized constructs that embody genre hybridity, moral ambiguity, and existential flair.

What makes both films timeless is their blend of aesthetic experimentation and philosophical depth. Whether it is Fincher’s use of hyper-stylized, gritty urban mise-en-scène and nihilistic voiceover narration, or Tarantino’s pop-cultural pastiche, intertextual references, and ironic juxtaposition of violence and humour—these are not just stylistic gimmicks but formal articulations of a postmodern worldview.

Influence and Legacy

The legacy of Fight Club and Pulp Fiction is expansive. Their stylistic and thematic DNA can be traced in numerous films across the globe. In Hollywood, films such as American Psycho (2000), Memento (2000), Requiem for a Dream (2000), and The Machinist (2004) clearly bear the imprint of Fight Club’s unreliable narration, hallucinatory aesthetics, and psychological depth. Christopher Nolan’s Memento, in particular, exemplifies the postmodern condition of fractured memory and subjective truth—concepts central to Fight Club’s split-identity narrative.

Tarantino’s influence on global cinema is even more ubiquitous. His love for nonlinear storytelling, genre-bending, and pop-culture-infused dialogue can be seen in films like Lock, Stock and Two Smoking Barrels (1998), Snatch (2000), and even Trainspotting (1996), which—though directed by Danny Boyle—shares Pulp Fiction’s punkish energy and moral irreverence.

Indian Cinematic Echoes

In India, several films have attempted to emulate or reinterpret the narrative and thematic paradigms set by these cult classics. Anurag Kashyap’s No Smoking (2007), Shaitan (2011), and Raman Raghav 2.0 (2016) reflect a deep engagement with Fight Club’s psychological disintegration and stylized violence. Kashyap himself has acknowledged the impact of both Fincher and Tarantino on his cinematic sensibility.

Sriram Raghavan’s Johnny Gaddaar (2007) and Andhadhun (2018) are further examples of how Indian cinema has adopted nonlinear narrative and genre subversion in ways reminiscent of Pulp Fiction. Even Delhi Belly (2011), with its profanity-laced dialogue, underworld absurdity, and ensemble cast, functions as an Indian homage to Tarantino’s storytelling techniques.

The Aura of the Characters

Characters such as Tyler Durden, Jules Winnfield, Vincent Vega, and Mia Wallace transcend the boundaries of narrative to become cultural archetypes. They exist in what Umberto Eco might call the "intertextual encyclopedia" of cinema—a space where their iconicism is constantly recycled, reinterpreted, and re-embodied. Tyler Durden, with his anti-establishment charisma and destructive liberation, continues to represent the chaos lurking beneath modern masculinity. Jules Winnfield, with his blend of Biblical fury and gangster cool, remains a figure of moral paradox and theatrical bravado.

Their aura, to borrow Walter Benjamin’s term, has not diminished but rather intensified with time. In the age of meme culture, remixes, and nostalgia-driven fandom, these characters have taken on a spectral afterlife. They are continually resurrected in digital discourse, cosplay, advertising, and even political commentary.

Final Thoughts

In the final analysis, Fight Club and Pulp Fiction endure not merely because of their themes or characters but because they mark a shift in cinematic ontology. They challenge viewers to rethink not just what a film says but how it says it. They anticipate a world where identity is performative, reality is fractured, and narrative is no longer a straight line but a Möbius strip.

To revisit them is not to relive the past, but to realize how much of our present was already anticipated by them. Their continued relevance is a testament to the power of cinema to both mirror and shape the cultural imagination.

Works Cited

Films:

American Psycho. Directed by Mary Harron, performances by Christian Bale and Willem Dafoe, Lions Gate Films, 2000.

Andhadhun. Directed by Sriram Raghavan, performances by Ayushmann Khurrana and Tabu, Viacom18 Motion Pictures, 2018.

Delhi Belly. Directed by Abhinay Deo, performances by Imran Khan and Vir Das, Aamir Khan Productions, 2011.

Fight Club. Directed by David Fincher, performances by Edward Norton, Brad Pitt, and Helena Bonham Carter, 20th Century Fox, 1999.

Johnny Gaddaar. Directed by Sriram Raghavan, performances by Neil Nitin Mukesh and Dharmendra, Adlabs Films, 2007.

Lock, Stock and Two Smoking Barrels. Directed by Guy Ritchie, performances by Jason Flemyng and Dexter Fletcher, Summit Entertainment, 1998.

Memento. Directed by Christopher Nolan, performances by Guy Pearce and Carrie-Anne Moss, Newmarket Films, 2000.

No Smoking. Directed by Anurag Kashyap, performances by John Abraham and Ayesha Takia, Eros International, 2007.

Pulp Fiction. Directed by Quentin Tarantino, performances by John Travolta, Uma Thurman, and Samuel L. Jackson, Miramax Films, 1994.

Raman Raghav 2.0. Directed by Anurag Kashyap, performances by Nawazuddin Siddiqui and Vicky Kaushal, Phantom Films, 2016.

Requiem for a Dream. Directed by Darren Aronofsky, performances by Ellen Burstyn and Jared Leto, Artisan Entertainment, 2000.

Shaitan. Directed by Bejoy Nambiar, performances by Rajeev Khandelwal and Kalki Koechlin, Viacom18 Motion Pictures, 2011.

Snatch. Directed by Guy Ritchie, performances by Jason Statham and Brad Pitt, Columbia Pictures, 2000.

Trainspotting. Directed by Danny Boyle, performances by Ewan McGregor and Robert Carlyle, PolyGram Filmed Entertainment, 1996.

Theoretical and Critical Texts:

Barthes, Roland. S/Z. Translated by Richard Miller, Hill and Wang, 1974.

Benjamin, Walter. The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction. Translated by Harry Zohn, Schocken Books, 1968.

Bakhtin, Mikhail. The Dialogic Imagination: Four Essays. Edited by Michael Holquist, translated by Caryl Emerson and Michael Holquist, University of Texas Press, 1981.

Baudrillard, Jean. Simulacra and Simulation. Translated by Sheila Faria Glaser, University of Michigan Press, 1994.

Debord, Guy. The Society of the Spectacle. Translated by Donald Nicholson-Smith, Zone Books, 1994.

Eco, Umberto. The Role of the Reader: Explorations in the Semiotics of Texts. Indiana University Press, 1979.

Nietzsche, Friedrich. Thus Spoke Zarathustra. Translated by R. J. Hollingdale, Penguin Classics, 1969.

No comments:

Post a Comment