Academic Year

2013-14:

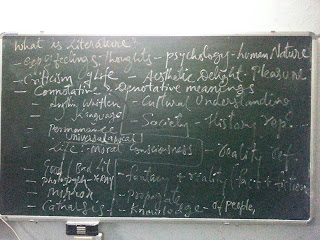

Post 4: Meaning

of Literature to Meaninglessness in Literature

During last two weeks (29 July to 10 August 2013

), I passed through a Tiresian sort of experience - 'throbbing between two lives' - from

Aristotle's concept of literature, his 'canonization' of literature, his giving

meaning to literature, his optimism in deathly tales of tragedies, his Oedipus-

the defiant against the Destiny; to Samuel Beckett's 'Nothing to be done', his

meaninglessness in literature, his pessimism in nothingness of human condition,

his Sisyphean happiness in human predicament of life where - "They give birth astride the grave, the light

gleams an instant, then it's night once more".

|

| Samuel Beckett |

|

| Aristotle |

In Semester 1, we ended

our discussion on Aristotle's 'Poetics'. I 'pitied' students' predicament and

concluded rather hurriedly, without giving more time for discussion and

engaging them in brainstorming age old Aristotelian concepts. I will show them

'fear' in the handful of dust when it comes to discuss 'possible and necessary'

questions. The presentations of important points discussed will be embedded

soon on this post so that late admissions and absent (physical as well as

mental) students can get themselves abreast.

In Semester 3, we are

still debating meanings in meaninglessness. Yes, it is, indeed, a difficult

task to switch over from Aristotle to Samuel Beckett. They both stand wide

apart in the basic concept of literature. Aristotle attempts, and quite

successfully, to defend and define first ever definition of Tragedy in

particular, and literature in general. Beckett’s plays presented life as

meaningless, and one that could simply end in casual slaughter.

Nevertheless, their difference

and polarization of ideas seems to be locking horns at each other. But in fact,

they deal with one and the same thing. Aristotle heavily relied on Sophocles’s ‘Oedipus

the Rex’ to bring home his arguments. And William Hutchings helps to connect

the dots. Let me quote at length from his book ‘Samuel Beckett’s Waiting for

Godot: A Reference Guide’ (Greenwood Publishing Group, 2005): “Since the

beginning of Western drama in ancient Greece in the 5th century B.C.,

three plays have generated, captivated more diverse interpretations, raised

more profound questions, captivated more audiences’ imaginations, and provoked

more arguments than any others – or even, quite possibly, more than all others

combined.” (I like the ‘shape of this sentence’. I borrow this from what Samuel

Beckett once wrote: “I am interested in the shape of ideas even if I do not

believe in them. There is a wonderful sentence in Augustine. . . “Do not

despair; one of the thieves was saved. Do not presume; one of the thieves was

damned.” That sentence has a wonderful shape. It is the shape that matters.”). Let us continue with Hitchings: “The fist,

Sophocles’s ‘Oedipus Rex’ (also known as ‘Oedipus Tyrannus’ or ‘Oedipus the

King’, was written in the fifth century B.C. in ancient Athens; the second, William

Shakespeare’s ‘Hamlet’, was first performed in London circa 1602; the third is

Samuel Beckett’s ‘Waiting for Godot’, which had its premiere in a very small

theatre in Paris in 1953. Each of these plays has a seemingly endless ability

to fascinate – and to perplex – its audiences, in part because its plot raises

questions for which there can be no easy answers or final resolutions: Did

Oedipus have free will in taking the actions that he did, even when he unknowingly

killed his father? Or was his fate entirely determined or predestined by the

Gods? Is Prince Hamlet mad, or is he not? Is the Ghost that he sees real, or is

it NOT? If real, is it telling the truth, or is it not? And, most strangely of

all, why are these two trams on this desolate landscape waiting beside a tree

for Mr. Godot whom they might not recognize and who does not – and may not – arrive?

Why isn’t much ‘happening’ here? What’s it meant to mean?”.

He further writes: “One

reason for the three plays’ continuing appeal is that each challenges its

audiences and its readers to think about profound questions about the naute of

the world in which we live; about the meaning of life itself; and , especially,

aobut how we know what we think we know about the universe, about other people,

and even about ourselves. Each in its own way embodies issues that have vexed

philosophers and theologians for years. ‘Oedipus Rex’ asks us to consider

whether gods or humans are fundamentally in control of the world; whether we

all have destinies that are inexorable, unavoidable, and preordained; and

whether there are circumstances in which we can – or even should – try to defy

the will of the gods and the edicts that they issue. ‘Hamlet’, similarly,

questions the ‘kind’ of universe we live in – whether justice can be found in

this world or the next (if at all), and whether we can ever know with certainty

the truth of our situations and then act with moral responsibility when and if

we think we do. ‘Waiting for Godot’, in many ways, simply extends those

uncertainties: why are we here? Are we alone in an uncaring universe, or not?

What are we to do while we are here? How can we know? And, ultimately, what

does it matter?

However profound the

questions that they raise and however disturbing the answers that they provoke,

these plays are fundamentally ‘not’ philosophical treatises or sermons. The

source of their perennial popular appeal lies, emphatically, elsewhere: despite

quite dissimilar styles, they share uniquely theatrical eloquences, a poetry

that is embodied in performance, conveyed not only through language but through

the predicament which Oedipus, Hamlet and two Tramps suffers”.(Italic words

are mine.)

(More to follow . . .)

Questions from students:

However, there were many questions raised and settled in the class, some dusted off, the two

with which I came home are:

1) If patriarchy 'conditions' languages, why is it called ‘mother

language’ and

2) If ‘Waiting for Godot’ deals with meaninglessness, why do we

say that the meaning of the play in meaninglessness and nothingness and .

. so and so on?

unknown to the dangers and it started playing with whiskers of the lion. Soon the lion woke up and roared angrily. The rat

started trembling. The lion was ready to svour the rat. The rat begged the lion to pardon and promised to help him in the

hours of need. At that time, the arogant lion smugged at the rat and left it alive. After some days the lion was trapped

by hunter in the net. The lion began to roar for help. soon the rat came with fellow friends and saved the life of lion.

And then they were friends forever.

The moral of the story is:

- One never knows how one can be helpful to others.

There he saw a lion.Unknown to the dangers of lion,he climbed over the body of the lion and started playing with his whiskers.

suddenly,the lion woke up and roared in anger.The rat was trembling in fear.Watching a trembling rat,the lion pitied him.The rat was ashamed

for his deed and begged to be pardoned.He also promissed the lion that he will help him in his critacal times.

The lion,in a mood of disgust smugged at rat ang left him alive.Then one day a group of hunters trapped the lion in a net.

A poor lion roared for help.As soon as the rat came to know about the trapping of lion,he came with a few friends and cut the

net.In this way he saved the lion.After that incident,they remained friends forever.

THE MORAL OF THE STORY:

1.A friend in need is a friend indeed.

2.Never underestimate anyone in your life because you never know how one can be helpful to others.

3.friendship is like water,no shape,no place,no

taste.But it is still essential for living.

But,how can a small creature help 'A KING'?.The king smugged the rat and gave him a chance to live.

The flow of time never remains the same.After few days The king was trapped by hunters in the net.It was so called pity of him.He craved and roared for help.The rat,being a being of blood and flesh,without thinking anything came with fellow friends and anyhow managed to save the King by cutting the stings of tne net.Only afterwards the lion understood the value of friendship and became the friends forever.