Gerard Genette: Structuralism and Literary Criticism

Part I

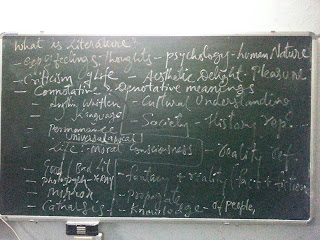

What is structuralism? How is it applied to the study of literature?

Structuralism (Structuralist Criticism): It is the offshoot of certain developments in linguistics and anthropology. Saussure’s mode of the synchronic study of language was an attempt to formulate the grammar of a language from a study of parole. Using the Saussurean linguistic model, Claude Levi-Strauss examined the customs and conventions of some cultures with a view of arriving at the grammar of those cultures. Structuralist criticism aims at forming a poetics or the science of literature from a study of literary works. It takes for granted ‘the death of the author’; hence it looks upon works as self-organized linguistic structures. The best work in structuralist poetics has been done in the field of narrative.

In literary theory, structuralism is an approach to analyzing the narrative material by examining the underlying invariant structure. For example, a literary critic applying a structuralist literary theory might say that the authors of West Side Story did not write anything "really" new, because their work has the same structure as Shakespeare's Romeo and Juliet. In both texts a girl and a boy fall in love (a "formula" with a symbolic operator between them would be "Boy + Girl") despite the fact that they belong to two groups that hate each other ("Boy's Group - Girl's Group" or "Opposing forces") and conflict is resolved by their death.

The versatility of structuralism is such that a literary critic could make the same claim about a story of two friendly families ("Boy's Family + Girl's Family") that arrange a marriage between their children despite the fact that the children hate each other ("Boy - Girl") and then the children commit suicide to escape the arranged marriage; the justification is that the second story's structure is an 'inversion' of the first story's structure: the relationship between the values of love and the two pairs of parties involved have been reversed.

Structuralistic literary criticism argues that the "novelty value of a literary text" can lie only in new structure, rather than in the specifics of character development and voice in which that structure is expressed.

Gerard Genette and Structuralistic Criticism

Gerard Genette writes at the outset in his essay ‘Structuralism and Literary Criticism’ that methods developed for the study of one discipline could be satisfactorily applied to the study of other discipline as well. This is what he calls “intellectual bricolage[i]’, borrowing a term from Claude Levi-Strauss. This is precisely so, so far as structuralism is concerned. Structuralism is the name given to Saussure’s approach to language as a system of relationship. But it is applied also to the study of philosophy, literature and other sciences of humanity.

Structuralism as a method is peculiarly imitable to literary criticism which is a discourse upon a discourse[ii]. Literary criticism in that it is meta-linguistic in character and comes into being / existence as metaliterature. In his words: “it can therefore be metaliterature, that is to say, ‘a literature of which literature is the imposed object’.” That is, it is literature written to explain literature and language used in it to explain the role of language in literature.

In Genette’s words, ‘if the writer questions the universe, the critic questions literature, that is to say, the universe of signs. But what was a sign for the writer (the work) becomes meaning for the critic (since it is the object of the critical discourse), and in another way what was meaning for the writer (his view of the world) becomes a sign for the critic, as the theme and symbol of a certain literary nature’. Now this being so, there is certain room for reader’s interpretation. Levi-Strauss is quite right when he says that the critic always puts something of himself into the works he read.

The Structuralist method of criticism:

Literature, being primarily a work of language, and structuralism in its part, being preeminently a linguistic method, the most probable encounter should obviously take place on the terrain of linguistic material. Sound, forms, words and sentences constitute the common object of the linguist and the philologist to much an extent that it was possible, in the early Russian Formalist movement, to define literature as a mere dialect, and to envisage its study as an annex of general dialectology.

Traditional criticism regards criticism as a message without code; Russian Formalism regards literature as code without message. Structuralism by structural analysis makes it possible to uncover the connection that exists between a system of forms and a system of meanings, by replacing the search for term by term analysis with one for over all homologies (likeness, similarity)”.

Meaning is yielded by the structural relationship within a given work. It is not introduced from outside. Genette believed that the structural study of ‘poetic language’ and of the forms of literary expression cannot reject the analysis of the relations between code and message. The ambition of structuralism is not confined to counting feet and to observe the repetition of phonemes: it must also study semantic (word meaning) phenomena which constitute the essence of poetic language. It is in this reference that Genette writes: “one of the newest and most fruitful directions that are now opening up for literary research ought to be the structural study of the ‘large unities’ of discourse, beyond the framework – which linguistics in the strict sense cannot cross – of the sentence.” One would thus study systems from a much higher level of generality, such as narrative, description and the other major forms of literary expression. There would be linguistics of discourse that was a translinguistics.

Genette empathetically defines Structuralism as a method is based on the study of structures wherever they occur. He further adds, “But to begin with, structures are not directly encountered objects – far from it; they are systems of latent relations, conceived rather than perceived, which analysis constructs as it uncovers them, and which it runs the risk of inventing while believing that it is discovering them.” Furthermore, structuralism is not a method; it is also what Ernst Cassirer calls a ‘general tendency of thought’ or as others would say (more crudely) an ideology, the prejudice of which is precisely to value structures at the expense of substances.

Genette is of the view that any analysis that confines itself to a work without considering its sources or motives would be implicitly structuralist, and the structural method ought to intervene in order to give this immanent study a sort of rationality of understanding that would replace the rationality of explanation abandoned with the search of causes. Unlike Russian Formalist, Structuralists like Genette gave importance to thematic study also. “Thematic analysis”, writes Genette, “would tend spontaneously to culminate and to be tested in a structural synthesis in which the different themes are grouped in networks, in order to extract their full meaning from their place and function in the system of the work.” Thus, structuralism would appear to be a refuge for all immanent criticism against the danger of fragmentation that threatens thematic analysis.

Genette believes that structural criticism is untainted by any of the transcendent reductions of psychoanalysis or Marxist explanation. He further writes, “It exerts, in its own way, a sort of internal reduction, traversing the substance of the work in order to reach its bone-structure: certainly not a superficial examination, but a sort of radioscopic penetration, and all the more external in that it is more penetrating.”

Genette observes relationship between structuralism and hermeneutics also. He writes: “thus the relation that binds structuralism and hermeneutics together might not be one of mechanical separation and exclusion, but of complementarity: on the subject of the same work, hermeneutic criticism might speak the language of the assumption of meaning and of internal recreation, and structural criticism that of distant speech and intelligible reconstruction.” They would, thus, bring out complementary significations, and their dialogue would be all the more fruitful.

Thus to conclude we may say, the structuralist idea is to follow literature in its overall evolution, while making synchronic cuts at various stages and comparing the tables one with another. Literary evolution then appears in all its richness, which derives from the fact that the system survives while constantly altering. In this sense literary history becomes the history of a system: it is the evolution of the functions that is significant, not that of the elements, and knowledge of the synchronic relations necessarily precedes that of the processes.

Part II

Application of Structuralism:

Gérard Genette (born 1930) is a French literary theorist, associated in particular with the structuralist movement and such figures as Roland Barthes and Claude Lévi-Strauss, from whom he adapted the concept of bricolage.

He is largely responsible for the reintroduction of a rhetorical vocabulary into literary criticism, for example such terms as trope and metonymy. Additionally his work on narrative, best known in English through the selection Narrative Discourse: An Essay in Method, has been of importance. His major work is the multi-part Figures series, of which Narrative Discourse is a section.

His international influence is not as great as that of some others identified with structuralism, such as Roland Barthes and Claude Lévi-Strauss; his work is more often included in selections or discussed in secondary works than studied in its own right. Terms and techniques originating in his vocabulary and systems have, however, become widespread, such as the term paratext for prefaces, introductions, illustrations or other material accompanying the text, or hypotext for the sources of the text.

This outline of Genette's narratology is derived from Narrative Discourse: An Essay in Method. This book forms part of his multi-volume work Figures I-III. The examples used in it are mainly drawn from Proust's epic In Search of Lost Time. One criticism which had been used against previous forms of narratology was that they could deal only with simple stories, such as Vladimir Propp's work in Morphology of the Folk Tale. If narratology could cope with Proust, this could no longer be said.

Below are the five main concepts used by Genette in Narrative Discourse: An Essay in Method. They are primarily used to look at the syntax of narratives, rather than to perform an interpretation of them.

Say a story is as follows: a murder occurs (event A); then the circumstances of the murder are revealed to a detective (event B), finally the murderer is caught (event C).

Arranged chronologically the events run A1, B2, C3. Arranged in the text they may run B1 (discovery), A2 (flashback), C3 (resolution).

This accounts for the 'obvious' effects the reader will recognise, such as flashback. It also deals with the structure of narratives on a more systematic basis, accounting for flash-forward, simultaneity, as well as possible, if rarely used effects. These disarrangements on the level of order are termed 'anachrony'.

The separation between an event and its narration allows several possibilities.

- An event can occur once and be narrated once (singular). (Give me more – Oliver)

- 'Today I went to the shop.'

- An event can occur n times and be narrated once (iterative). (valour of Macbeth, sleepless nights)

- 'I used to go to the shop.'

- An event can occur once and be narrated n times (repetitive). (Tess’s molestation and its aftereffect)

- 'Today I went to the shop' + 'Today he went to the shop' etc.

- An event can occur n times and be narrated n times (multiple). (Moll’s escapades into immoral behaviour)

- 'I used to go to the shop' + 'He used to go to the shop' + 'I went to the shop yesterday' etc.

The separation between an event and its narration means that there is discourse time and narrative time. These are the two main elements of duration.

- "Five years passed", has a lengthy discourse time, five years, but a short narrative time (it only took a second to read).

- James Joyce's novel Ulysses has a relatively short discourse time, twenty-four hours. Not many people, however, could read Ulysses in twenty-four hours. Thus it is safe to say it has a lengthy narrative time.

Voice is concerned with who narrates, and from where. This can be split four ways.

- Where the narration is from

- Intra-diegetic: inside the text. eg. Wilkie Collins' The Woman in White(1859)(Chocolate, Musafir)

- Extra-diegetic: outside the text. eg. Thomas Hardy's Tess of the D'Urbervilles

- Is the narrator a character in the story?

- Hetero-diegetic: the narrator is not a character in the story. eg. Homer's The Odyssey (Samay in Mahabharat,)

- Homo-diegetic: the narrator is a character in the story. eg. Emily Brontë's Wuthering Heights (Moll Flanders) Pilgrim’s Progress

Genette said narrative mood is dependent on the 'distance' and 'perspective' of the narrator, and like music, narrative mood has predominant patterns. It is related to voice.

Distance of the narrator changes with narrated speech, transposed speech and reported speech.

Perspective of the narrator is called focalization. Narratives can be non-focalized, internally focalized or externally focalized.

Genette, G (1980) Chapter 4: 'Mood' in Narrative Discourse, pp. 161 - 211, 1980, New York, Cornell University Press.

Wikipedia contributors. "Gérard Genette." Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, 5 Mar. 2015. Web. 21 Mar. 2015.

Roland Barthes - Mythologies

The other major figure in the early phase of structuralism was Roland Barthes, who applied the structuralist method to the general field of modern culture. He examined modern France (of the 1950s) from the standpoint of a cultural anthropologist in a little book called Mythologies which he published in France in 1957. This looked at a host of items which had never before been subjected to intellectual analysis, such as: the difference between boxing and wrestling; the significance of eating steak and chips; the styling of the Citroen car; the cinema image of Greta Garbo's face; a magazine photograph of an Algerian soldier saluting the French flag. Each of these items he placed within a wider structure of values, beliefs, and symbols as the key to understanding it. Thus, boxing is seen as a sport concerned with repression and endurance, as distinct from wrestling, where pain is flamboyantly displayed. Boxers do not cry out in pain when hit, the rules cannot be disregarded at any point during the bout, and the boxer fights as himself, not in the elaborate guise of a make-believe villain or hero. By contrast, wrestlers grunt and snarl with aggression, stage elaborate displays of agony or triumph, and fight as exaggerated, larger than life villains or super-heroes. Clearly, these two sports have quite different functions within society: boxing enacts the stoical endurance which is sometimes necessary in life, while wrestling dramatises ultimate struggles and conflicts between good and evil. Barthes's approach here, then, is that of the classic structuralist: the individual item is 'structuralised', or 'contextualised by structure', and in the process of doing this layers of sigificance are revealed. (Source: Peter Barry: An Introduction to Theory)

Roland Barthes - S/Z

Structuralist criticism: examples

These examples are based on the methods of literary analysis described and demonstrated in Barthes's book S/Z, published in 1970. This book, of some two hundred pages, is about Balzac's thirty-page story 'Sarrasine'. Barthes's method of analysis is to divide the story into 561 lexies', or units of meaning, which he then classifies using five 'codes', seeing these as the basic underlying structures of all narratives. So in terms of our opening statement about structuralism (that it aims to understand the individual item by placing it in the context of the larger structure to which it belongs) the individual item here is this particular story, and the larger structure is the system of codes, which Barthes sees as generating all possible actual narratives, just as the grammatical structures of a language can be seen as generating all possible sentences which can be written or spoken in it. I should add that there is a difficulty in taking as an example of structuralism material from a text by Barthes published in 1970, since 1970 comes within what is usually considered to be Barthes's post-structuralist phase, always said to begin (as in this book) with his 1968 essay 'The Death of the Author'. My reasons for nevertheless regarding S/Z as primarily a structuralist text are, firstly, to do with precedent and established custom: it is treated as such, for instance, in many of the best known books on structuralism (such as Terence Hawkes's Structuralism and Semiotics, Robert Scholes's Structuralism in Literature, and Jonathan Culler's Structuralist Poetics). A second reason is that while S/Z clearly contains many elements which subvert the confident positivism of structuralism, it is nevertheless essentially structuralist in its attempt to reduce the immense complexity and diversity possible in fiction to the operation of five codes, however tongue-in-cheek the exercise may be taken to be. The

truth, really, is that the book sits on the fence between structuralism and post-structuralism: the 561 lexies and the five codes are linked in spirit to the 'high' structuralism of Barthes's 1968 esssay 'Analysing Narrative Structures', while the ninety-three interspersed digressions, with their much more free-wheeling comments on narrative, anticipate the 'full' post-structuralism of his 1973 book The Pleasure of the Text. The five codes identified by Barthes in S/Z are:

1. The proairetic code This code provides indications of actions. ('The ship sailed at midnight' 'They began again', etc.)

2. The hermeneutic code This code poses questions or enigmas which provide narrative suspense. (For instance, the sentence 'He knocked on a certain door in the neighbourhood of Pell Street' makes the reader wonder who lived there, what kind of neighbourhood it was, and so on).

(Read this to understand the difference between proairetic and hermeneutic)

(Read this to understand the difference between proairetic and hermeneutic)

3. The cultural code This code contains references out beyond the text to what is regarded as common knowledge. (For example, the sentence 'Agent Angelis was the kind of man who sometimes arrives at work in odd socks' evokes a preexisting image in the reader's mind of the kind of man this is - a stereotype of bungling incompetence, perhaps, contrasting that with the image of brisk efficiency contained in the notion of an 'agent'.).

4. The semic code This is also called the connotative code. It is linked to theme, and this code (says

Scholes in the book mentioned above) when organised around a particular proper name constitutes a

'character'. Its operation is demonstrated in the second example, below.

5. The symbolic code This code is also linked to theme, but on a larger scale, so to speak. It consists of contrasts and pairings related to the most basic binary polarities - male and female, night and day, good and evil, life and art, and so on. These are the structures of contrasted elements which structuralists see asfundamental to the human way of perceiving and organising reality.

For better understanding of these codes, read this: https://courses.nus.edu.sg/course/elljwp/5codes.htm

For better understanding of these codes, read this: https://courses.nus.edu.sg/course/elljwp/5codes.htm

Part III

What do Struturalist critics do?

1. They analyse (mainly) prose narratives, relating the text to some larger containing structure, such as:

(a) the conventions of a particular literary genre, or

(b) a network of intertextual connections, or

(c) a projected model of an underlying universal narrative structure, or

(d) a notion of narrative as a complex of recurrent patterns or motifs.

2. They interpret literature in terms of a range of underlying parallels with the structures of language, as described by modern linguistics. For instance, the notion of the 'mytheme', posited by Levi-Strauss, denoting the minimal units of narrative 'sense', is formed on the analogy of the morpheme, which, in linguistics, is the smallest unit of grammatical sense. An example of a morpheme is the 'ed' added to a verb to denote the past tense.

3. They apply the concept of systematic patterning and structuring to the whole field of Western culture, and across cultures, treating as 'systems of signs' anything from Ancient Greek myths to brands of soap powder.

Barry, Peter. An introduction to literary and cultural theory

Activity:

- Quiz: Click here to appear in the Quiz based on Structuralism and Literary Criticism

- Think and Write: Being a structuralist critic, how would you analyse literary text or TV serial or Film? You can select any image or TV serial or film or literary text or advertisement. Apply structuralist method and post your write up on your blog. Give link of that blog-post in the comment section under this blog.

[i] Claude Levi-Strauss, The Savage Mind (Chicago, 1966).p.17.

[ii] Roland Barthes, Critical Essays. p.258.

[iii] Introduction to Structuralism: V. S. Seturaman (Contemporary Criticism: An Anthology. Macmillan)

[iii] Introduction to Structuralism: V. S. Seturaman (Contemporary Criticism: An Anthology. Macmillan)

.jpg)